Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) has received a three-year, $25-million award from the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory (CCDC-ARL) to advance a 3D printing technique that could be used to repair vehicles and other critical technology in the field, avoiding the sometimes extensive wait for new parts and increasing the readiness of military units.

The new award builds on the university’s deep and distinctive experience with powder metallurgy and computational tools for materials design gained with nearly $30 million in previous Army funding.

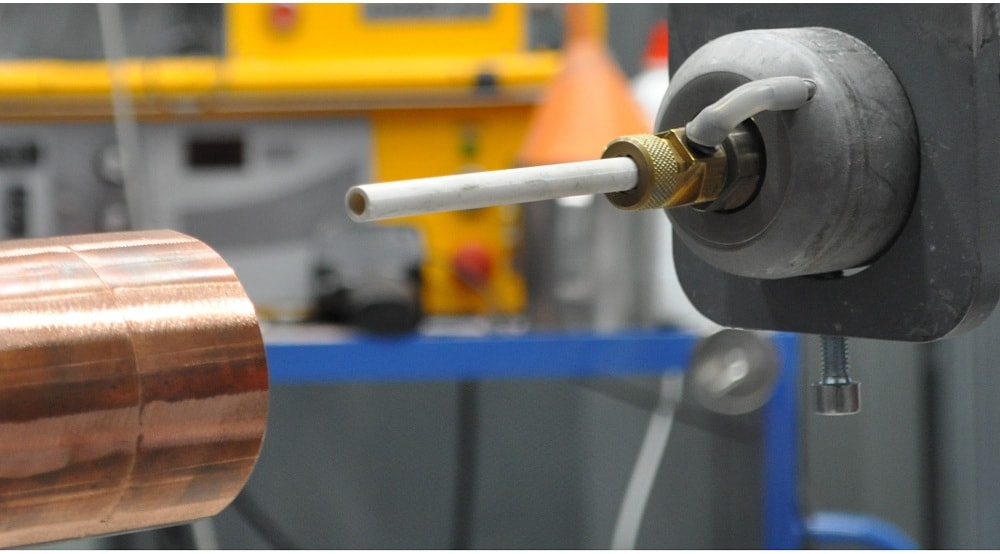

The current Army Research Laboratory (ARL) award will focus on a technique called cold spray, which can be used to repair metal parts or even make new parts from scratch by building up metal layer by layer in a process known as additive manufacturing, commonly known as 3D printing. Cold spray uses a pressurized gas to accelerate metal powders to near supersonic speeds. The force of impact causes the powders to adhere to the metal upon impact. There is no need to first melt the powders. The process can be reduced to a portable handheld applicator, which makes it attractive for use in the field.

“The Army is interested in cold spray 3D printing as a repair technique,” said Danielle Cote, assistant professor of materials science and engineering and director of WPI’s Center for Materials Processing Data , who is the principal investigator for the ARL project. “It’s cheaper to repair a part than to replace it, and you get the equipment back in service faster. The Army’s primary interest is unit readiness. If you’re on a mission and need to move quickly to a safer place, and a critical part on your vehicle breaks, you’re stuck unless you can repair it quickly. That’s where cold spray comes in.”

WPI’s primary focus in this research will be on developing, characterizing, and testing new alloys optimized for use in cold spray. Cote said the characteristics of the metal powders used in cold spray are critically important since the metal is not melted before being sprayed onto a part that needs repair, nor is it heat treated after application. “With most manufacturing methods, metal alloys are altered by first being melted, and then often heat treated to strengthen or otherwise improve their properties. With cold spray, what you end up with in the repair is exactly what you start with, so the characteristics of the powders are quite important.”

WPI will develop and study powders using a variety of state-of-the-art equipment, including instruments acquired as part of the new ARL award. These include tools to study the chemical and structural properties of the powders at the scale of nanometers, such as a SEM/EDS (scanning electron microscope and energy dispersive spectroscopy) unit, a synchronous laser diffraction and dynamic image particle analyzer to determine powder morphologies, and nanoindenters to measure nano-scaled mechanical properties.

The WPI research team, which includes postdoctoral fellow Kyle Tsaknopoulos, will also work with several subcontractors, including the University of California Irvine, the University of Massachusetts Lowell, Penn State University, and Solvus Global. A spin-off of WPI including two recent WPI PhD recipients in materials science and engineering—Aaron Birt (2017) and Sean Kelly (2018)—Solvus Global will provide commercially available powders and modify them to meet the research team’s specifications so they can be tested in actual cold spray applications.

While the primary focus of the ARL award will be alloys for repairs, Cote noted that “cold spray is a foundational technology with a wide variety of applications, in the military and beyond.” As part of the research program, a team of co-principal investigators from multiple disciplines at WPI will explore some promising new applications, including the use of cold spray to apply copper coatings to give equipment antibacterial properties.

Researchers in WPI’s robotics engineering program will explore the use of multi-axes robots to automate cold spray. “The Army is especially interested in portable cold spray systems, but the technology can also be used on a larger scale—in industry, for example—and it will be exciting to see how robots can help expand the use of this and other additive manufacturing processes.

“I think there is much potential for this technique. With the work we will be doing with powder development, in robotics, and in a number of other areas, I think we are going to go a long way with cold spray. There really are endless possibilities.”